Today the artist Helen Saunders (1885-1963) is well-represented in public collections. The Courtauld Gallery holds twenty of her paintings; Tate owns a further eight, the Victoria and Albert Museum has two and the Ashmolean Museum one, while across the Atlantic the David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago possesses four of her works. As an acknowledged pioneer of abstraction her work has been included internationally in exhibitions in New York, Hanover, Toulouse, Venice and Paris as well as in London. Even so, her name is little-known, even to those familiar with 20th century British art. Why has she remained in the shadows?

Helen Beatrice Saunders was born into a professionally successful family (her grandfathers were respectively the Dean of Peterborough Cathedral, and a doctor and former Mayor of Peterborough and her father despite early health issues became the principal Rating Agent of the Great Western Railway). Her upbringing was sheltered; she and her sister were home-educated by governesses and tutors with the expectation that they would either marry or dedicate their lives to 'good works' in the voluntary sector. Nonetheless her family supported her decision to study art (an aunt, Agnes Saunders, had earlier studied art at the South Kensington Schools with the intention of painting missionary churches in Africa, and one of her cousins, Reynolds Ball, had dropped out of Cambridge to attend a studio in Paris). In around 1903-1906 she attended a teaching studio for women in Ealing run by Slade graduate Rosa Waugh Hobhouse (1882- 1971). She then studied briefly at the Slade (but found the teaching there unhelpful) and at an unknown time took classes at the Central School of Arts and Crafts.

In 1911, after her maternal grandfather's death, Saunders parents were able to settle a modest income from investments on both their daughters. This gave her (at age 26), the means to migrate from the comfortable family home in Ealing to independence in rented rooms in Chelsea (Rosa Waugh Hobhouse commented on the 'primitive arrangements' there). She began to engage with contemporary issues, participating in the WSPU's 1911 'Coronation' procession standing in for one of 700 women who had been imprisoned for their suffragette activities. Her artistic horizons expanded; she was impressed by Roger Fry's Post Impressionist exhibitions at the Grafton Gallery (1910 and 1912). Fry in turn recognised the quality of her paintings and selected two of them for 'Quelques Independants anglais' (May 1912), an exhibition that he curated at the radical Galerie Barbazanges in Paris, and went on to include an oil now identified as Barn and Road in his 'First Grafton Group Exhibition' (March 1913) in London in. Paintings that she showed with the AAA (Allied Artists Association) in July 1912 were mentioned in reviews by Fry and Clive Bell. Alignment with what later became known as the 'Bloomsbury' strand within the British avant-garde seemed assured.

Saunders, Barn and Road, oil on canvas, 1912 (Pallant House)

Though describing herself as 'a solitary by nature', Saunders also became close to several future members of the Vorticist group - Wyndham Lewis, who made several drawings of her in 1912 and 1913, Jessie (later Jessica) Dismorr, whose Chelsea studio was close to her lodgings, and Frederick Etchells, for whom the designer Madge Pulsford, already one of her friends, was to pose in 1912. As she later explained to the art historian William Wees (Sept. 1962) Roger Fry had 'put some of the ideas already working in Paris into circulation in London', and in 1913 her (now lost) painting The Oast House, shown at the Allied Artists' Association, was described by a visitor to the exhibition as 'Cubist'.

Though not directly involved with Fry's Omega Workshops, Saunders may initially have been critical of Lewis's acrimonious secession in October 1913, since their already-close relationship foundered at that time. Nonetheless, by the following spring she was closely involved with setting up and running the Rebel Art Centre (March - June 1914), spearheaded by Lewis. She and Dismorr were the only two women among the eleven signatories of the radical Vorticist Manifesto, published in the first issue of the Vorticists' artistic and literary periodical BLAST (June 1914) and launched from the Rebel Art Centre. Saunders masked her participation by deliberately mis-spelling her surname as 'Sanders' so as not to upset her churchgoing family to whom she remained close while questioning their religious convictions. (At that time 'Blast', as an oath, was considered even more blasphemous than 'Damn').

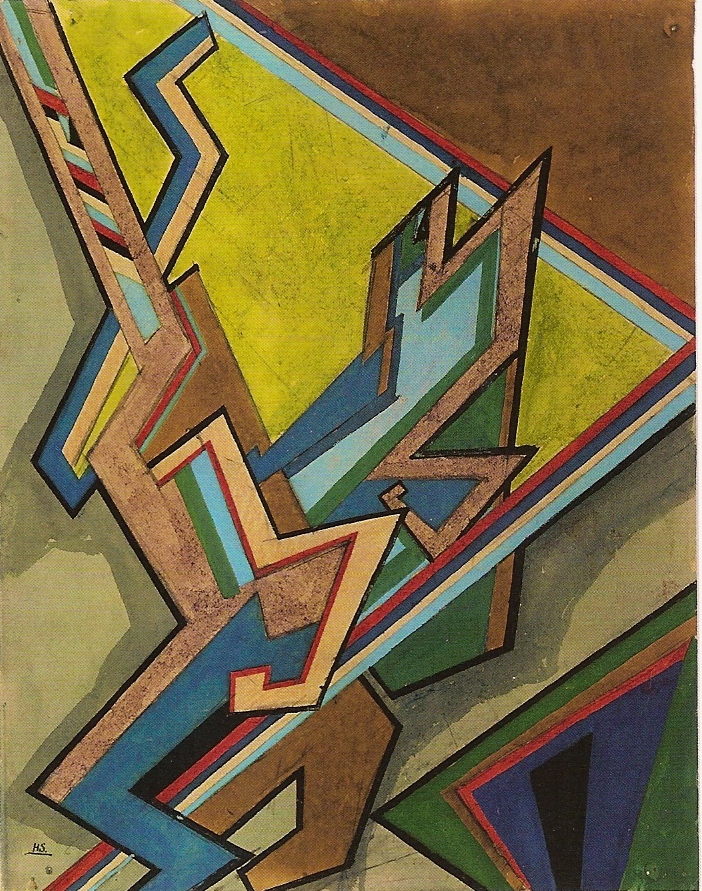

Saunders: The Rock Driller ink and watercolour, c. 1912-13 (Courtauld)

Saunders: The Rock Driller ink and watercolour, c. 1912-13 (Courtauld)

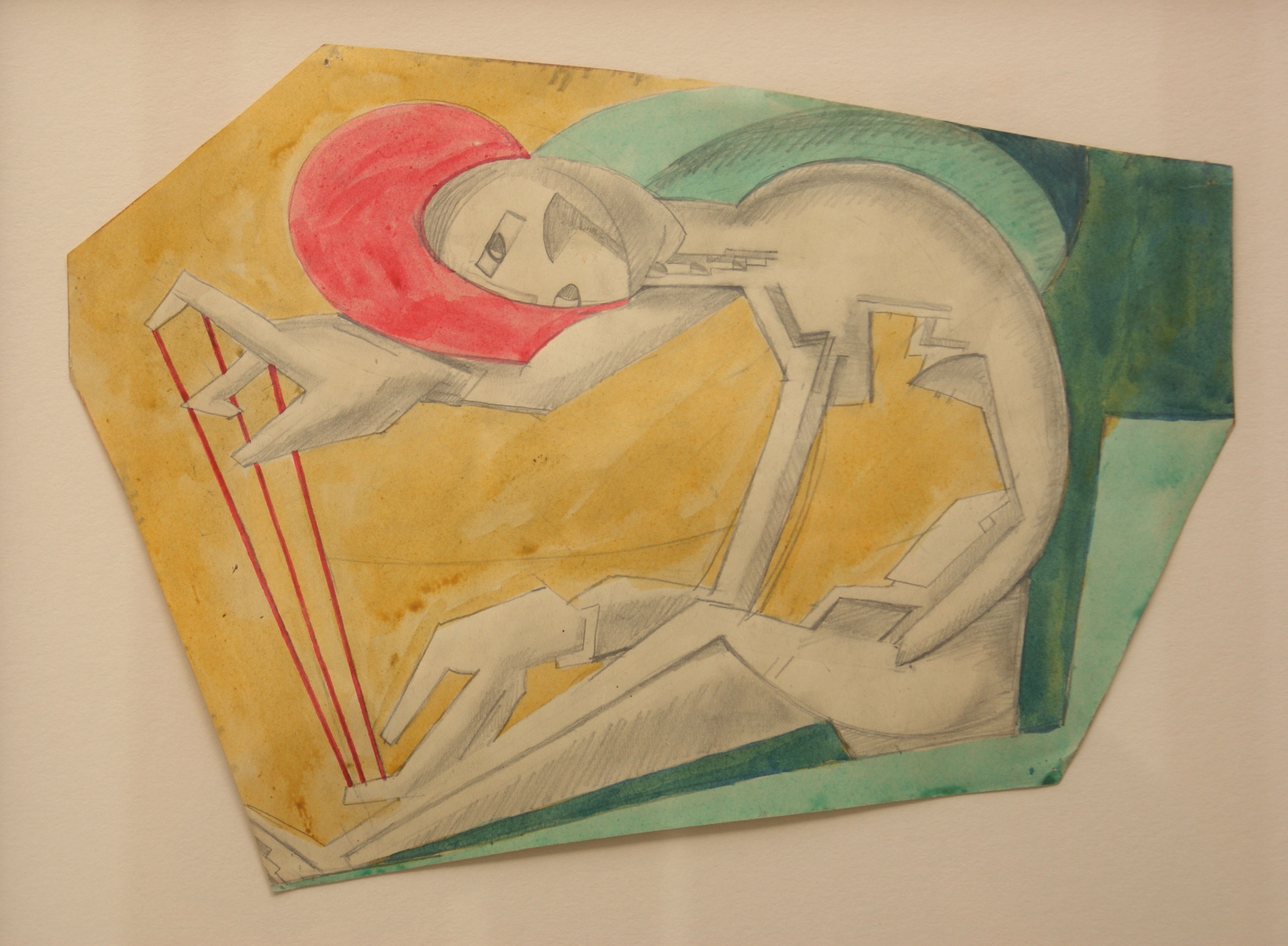

By 1914 Saunders was enthusiastically exploring the challenges offered by the Vorticists' re-invention of visual language. Owing its genesis to Cubism and Futurism while more formally radical than either, Vorticist practice developed from the idea that since modern life was city-based and permeated by industrial and mechanical products, modern art should embody these characteristics. Vorticist images were therefore hard-edged and geometrical, constructed predominantly from straight lines occasionally offset by arcs, and in some cases were completely abstract. Saunders's 'Study with bending figure' may be symbolic self-portrait, signalling the engagement of her eyes, mind and hands in contemplating this new reality.

Saunders: Study with Bending Figure graphite and watercolour, c. 1913-14 (Courtauld)

Saunders: Study with Bending Figure graphite and watercolour, c. 1913-14 (Courtauld)

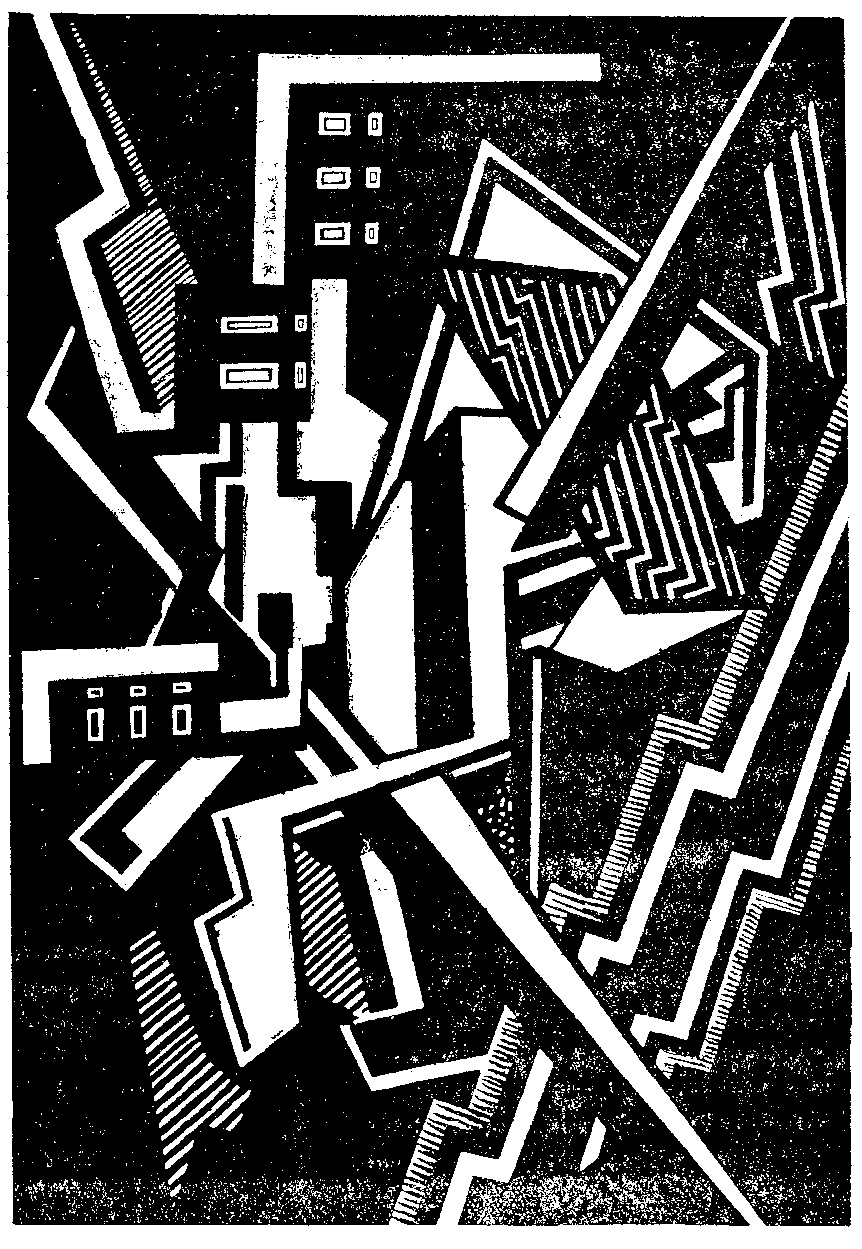

WW1 broke out less than two months after Vorticism's launch. Initially expected to be 'over by Christmas', its duration and unprecedented levels of carnage only gradually became evident. The second 'War Number' of BLAST, initially mooted by the artist Edward Wadsworth in August 1914, made a belated appearance in July 1915; Saunders and Dismorr, glimpsed in the first issue only as manifesto signatories, made significant visual and written contributions, and Saunders's Chelsea lodgings served as its distribution address. The issue had been planned to coincide with the Vorticists' first (and only) London exhibition at the Doré Galleries (June 1915), and Saunders contributed four oil paintings and two works on paper to this show. Her exhibited oils were all believed lost until 2019, when postgraduate researchers Becky Chipkin and Helen Kohn at the Courtauld Institute discovered that Lewis's large (56" x 40") oil portrait 'Praxitella' dating from 1920 (Leeds Art Gallery) was painted on top of Saunders's 'Atlantic City', one of the missing works. Saunders's own black-and-white version of the composition, published in BLAST 2, made this identification possible.

Saunders: Atlantic City, 1915 (line block reproduction BLAST 2)

Saunders: Atlantic City, 1915 (line block reproduction BLAST 2)

Lewis and Saunders became estranged in 1919, leading to a serious breakdown on Saunders's part. His obliteration of Saunders's most ambitious Vorticist composition was consistent with his sustained efforts (supported by his friend and admirer the Imagist poet Ezra Pound) to frame Vorticism as his own creation and to downplay the achievements of the movement's other participants and associates. The Vorticist exhibition at the Penguin Club in New York (1917), its contributions selected and shipped by Pound, comprised 46 works by Lewis but only 28 by all the other Vorticist exhibitors (Dismorr, Etchells, Roberts, Saunders and Wadsworth) combined. In his subsequent writings, culminating in his introduction to the catalogue of 'Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism' at the Tate Gallery (1956), Lewis went out of his way to dismiss his fellow-Vorticists as insignificant camp-followers, a narrative that remained dominant until the late 20thcentury.

While Pound regarded Lewis's work as the embodiment of the Vorticist paradigm, Saunders and her fellow-rebels found personal ways to assimilate Vorticist principles into their respective works. In Saunders's case this involved constant formal experiment; instead of developing and then maintaining a particular visual formula, she was intent on investigating the range of expressive possibilities that Vorticism seemed to promise. Her work, always personal, was thus more varied (and arguably uneven) than compositions by her friends Lewis, Wadsworth and Roberts. This diversity, later interpreted by the historian of Vorticism Richard Cork (1976) as 'female waywardness', was to contribute to Saunders's continuing professional obscurity.

At the end of 1917 Saunders, in a letter to her Vorticist friend and colleague Jessie Dismorr, wrote of her hope of 'perhaps inventing something', and the process of investigation and discovery rather than the development of a consistent, easily recognisable style was to continue to characterise her artistic output. Due perhaps to her protected upbringing, and undoubtedly to her reliable if increasingly modest private income, she did not seek recognition or produce paintings that were intended as marketable products. After Vorticism she returned to representation; to portraiture (mainly of friends), landscape (mostly in watercolour) and still life (often in oil). After 1920 she seldom exhibited except in local shows in Holborn, central London. A rare exception was her contribution of a landscape to the one exhibition held by the 'No Jury Art Club' which was set up by her friend Walter Richard Sickert in 1928 and dissolved by him in 1929. This exhibition (which showed works by mainly amateur artists from the East End alongside those of self-selected professionals) featured, perhaps coincidentally, works by two successful painters who had had a significant presence in Saunders's life - Sickert himself (whose proposal of marriage she had declined in c.1922) and Wyndham Lewis (who contributed a portrait of her to the show, probably one of four that he had drawn during a period of rapprochement in the winter of 1922-1923).

Saunders: View from studio window, watercolour, 1928-9 (Private coll.)

Saunders: View from studio window, watercolour, 1928-9 (Private coll.)

Today, around 250 paintings and drawings by Saunders are known, many unfinished or painted on the backs of others. Some are thought to have been lost when her flat in John Street, Holborn was bombed in 1940, and in 1956 she apologised to Tate that a small Vorticist oil that she had hoped to contribute to the Wyndham Lewis exhibition had been stolen. All but two of her sketchbooks have disappeared, and in her later years she often re-used her earlier canvases and boards. She probably destroyed paintings with which she felt dissatisfied, while others may have been disposed of when she and her sister sold the contents of the large family home in Oxford to a local antiques dealer (who was reputed to have retired on the proceeds) after their mother's death in 1956.

Saunders: Still life with vase, oil on hardboard, 1950s (Private coll.)

Saunders clearly gave little or no thought to her artistic legacy and would probably have been astonished by the posthumous interest in her early and Vorticist paintings by the curators of national collections. Nearly all her surviving works, spanning from the 1920s until her death (1st January 1963) were inherited by her sister Ethel. The majority of her sketches, her few preserved letters and other related materials have now been placed in Tate's archive, while most of her later paintings remain with members of her wider family. These works are undated and diverse in style and only one is signed. They bear witness to a life devoted to single-minded visual exploration and commitment to personal expression rather than to building a professional career or gaining recognition or acclaim. The forthcoming Catalogue Raisonné of her work, to be published by the Court Gallery, will provide the opportunity for the oeuvre of this hitherto overlooked artist to become more widely known and enjoyed.

References

Antliff, Mark and Greene, Vivien (eds). The Vorticists. (Tate Publishing, 2010)