When the writer V. S. Pritchett visited Paris as a young man in the 1920s he admitted to feeling initially angry with the ‘moderns’ remarking that they were ‘smashing up a culture just as I was becoming acquainted with it’. This violent confrontation between the old and the new was felt acutely by a whole generation of artists and writers during the first half of the twentieth-century. Yet for a significant few the destruction of the old order, with its assault on convention and academism, was an act of liberation. Kenneth Lauder was one of the British painters who felt instinctively drawn to those ‘who were trying to break new ground’ and as a student at the Royal College of Art in the 1930s he immersed himself in the work of Braque, Matisse and Picasso in open defiance of most of his tutors.

Born in Edinburgh just over a century ago in 1916, Lauder must have heard the sound of the Zeppelin raid over that city when more than twenty bombs were dropped in the space of forty minutes heralding the terror of a new form of warfare waged from the air. Whilst still an infant and perhaps in reaction to this fear his family moved briefly to the Isle of Bute before settling finally in the south of England. However, Lauder’s Scottish heritage remained a defining feature of his artistic character and his sense of tone and colour makes him akin to other progressive Scottish painters of his generation.

During the early 1930s, before attending the R.C.A., Lauder was fortunate to encounter the refined wisdom of Robert Medley at the Chelsea School of Art. As one of the youngest members of the Chelsea staff Medley had a natural empathy for the challenges facing young painters at a time of great change. Writing in this autobiography he articulated that critical moment:

The real day-to-day problem that young painters emerging from adolescence during the late twenties had to cope with was that the Tradition, even if it was seen to culminate in Cézanne, seemed already far distant and vague in outline. A work of art now could be made out of almost anything: old matchboxes, the shapes of guitars, and collaged sheets from Le Journal. A pipe, a loaf of bread, a packet of tobacco and a wine bottle became a “Holy Family”. The astonishing outburst of modernist creative vitality, temporarily held back during the war,also had a progressive political dimension. In reaction to the violence of the war arose ironically the aesthetics of the machine: the aeroplane provided a key image. The artist, like the airman-hero, allied to the new technology, would pilot his way to a new society.

Medley, who disliked the dogmatic ‘charisma’ of some art school tutors, must have been particularly enlightening — suggesting quietly to his pupils that the possibilities of visual expression were now endless. Graham Sutherland who was also teaching at Chelsea provided further inspiration — leading by example as one of the most distinctive and visionary English modernists of his time. As Lauder later wrote ‘the break from realism meant a freeing of the imagination unfettered by the subject matter’ providing the opportunity for artists to explore both different techniques, alternative subjects and abstraction.

Lauder’s drawings and paintings from his student days reveal a talented draughtsman entirely in command of traditional methods - indeed a sensitivity of line and touch is apparent throughout his sketchbooks and working drawings. However, before he could begin building on this solid foundation the outbreak of the Second World War interrupted his ambitions. Initially he resisted the idea of military service feeling strongly that he wanted to be engaged in ‘something constructive’ which for him led to joining the conscientious objectors working in agriculture producing food for the war effort. Lauder signed the Peace Pledge and for the first two years of the war he worked on a farm in Oxfordshire and it was not until 1942 that he had a change of heart, joining the R.A.F.V.R., to train as a pilot. His previous stance as a conscientious objector excluded him from combat operations so he spent the remainder of the war training pilots. It was his experiences in the air - particularly the training in North America - that were to influence his aesthetic preoccupations when he was finally able to return to his principal passion of painting. Witnessing vast landscapes from the air stimulated his visual perceptions, inspired reinterpretation and he was to draw from the ‘airborne’ experience repeatedly throughout the post-war years.

Keeping in mind Medley’s idea of the aeroplane signalling all that was new, it is fitting that Lauder’s first series of experimental paintings were concerned with elements of aircrafts deconstructed and reassembled into surreal objects floating in imagined landscapes. These small, colourful works on paper were completed during 1945 and they anticipated the pictorial explorations that Lauder wrestled with during the immediate post-war era. As exercises in the arrangement of form and colour they demonstrate Lauder’s natural facility for creating rhythm and pattern and he would later write that it was the combination of these qualities that really interested him. His passion for music, notably Bach, Debussy, Haydn and Schoenberg, was also a constant source of inspiration in his search for a visual flow enabling the freedom to invent and ‘accept new forms and new framework’. Lauder developed an early fascination with process and technique which determined his development through a number of distinct stylistic phases.

After war service Lauder, who was newly married, moved to the Isle of Man where he concentrated again on painting. He also collaborated with his wife weaving rugs, using jute, parachute cord and blackout curtain which were later exhibited at the Manchester City Art Gallery. This was a difficult period of adjustment - balancing his vocational aspirations with family responsibilities. Clearly the transition from the climate of war and military service to ordinary civilian routine was a critical challenge that faced a whole generation. Pursuing the life of an artist offered little stability and finding a means by which artists could find their way back to creative work was vital. Patrick Heron wrote about the isolation from Europe that artists felt during the war years and how British artists lost touch with the great innovators of the modern Paris School. Undoubtedly there was a loss of impetus that needed to be re-ignited.

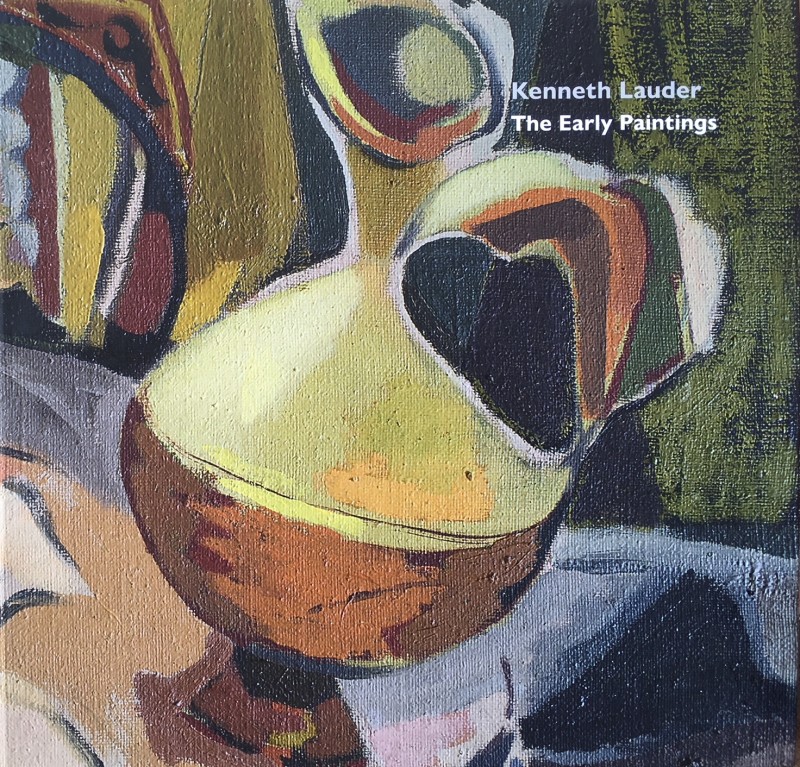

The Tate Gallery’s timely and impressive Braque exhibition of 1946 was a hugely significant event for many young British painters seeking creative guidance after a period of cultural introversion. The work that Braque completed during the war years was exhilarating showing ‘a new development in an immensely powerful art’ as Patrick Heron later observed. Braque’s studio was under constant watch by the Nazis during the occupation and feeling confined he worked tirelessly with ever greater ambition taking the still life theme to new heights of aesthetic exploration. He began his fish bowl series which provided a powerful but deeply poetic metaphor for the entrapment he and his countrymen felt. Like many of his contemporaries, Lauder was profoundly affected by the monumentality and ambition of Braque’s late work and throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s Lauder’s own work referenced the complex arrangement of objects what was such a defining feature of Braque’s late paintings. Braque’s experiments with texture and surface also suggested more possibilities for the way in which images could be made.

The arrangement of ordinary, everyday objects into formal aesthetic statements became Lauder’s obsession. All serious artists must be obsessed with their occupation - consumed by the process and dedicated to meaningful outcomes. Following Braque’s mantra ‘Reality only reveals itself when it is illuminated by a ray of poetry’ - Lauder’s early still lives are layered with probing subtleties both in colour and design and during the 1950s he began experimenting with texture adding weight and sculptural depth to the painted image.

Lauder first showed at the Redfern Gallery in 1950 and although he was never formally a part of groups or movements his work should be understood in the context of the decade immediately after the war when abstract art inspired young artists seeking a new visual language to express the violently altered post-war world. A notable friendship with Alan Reynolds suggests he was not isolated from his contemporaries and in his many years as an influential teacher of art he remained abreast of the latest innovative thinking.

Writing in the later 50s Lauder observed ‘It is not only the linear quality and pattern but the combination of this (and the acceptance) and proportion of shape that is of interest to me….. This is a new, and yet an old, world. It is visually full of joy. It has a vitality which no objective painting can, or could, have. It is on its toes - it dances’. It was this striving for the joys of felt experience that under-pinned all of Lauder’s experimentation and led to a seamless continuity between figurative and abstract episodes in his work.

In Lauder’s figurative paintings there is a warm, humanity completely without the sardonic elements that so often prevails amongst the more hard-edged modernists. There is no ‘hunger for ferocity’, only sensitivity and compassion. In paintings like ‘Boy with a Butterfly net’, ‘Girl in a Pink Dress’ and ‘The Bride’ Lauder celebrates his sitters never deriding them. Even his ‘Beast in Fury’ is somehow good natured and devoid of menace. This wise and forgiving spirit lies at the heart of all his paintings leaving the viewer with a sense of wonder and hope.

Lauder embraced painting and image making as the pathway to an inner freedom. To be immersed in the creative process is to experience a profound liberation - free of all social and conformist conventions. In a revealing note from the 50s he explored a facinating analogy - ‘To be freed, to give freely while painting is like copulation - it cannot achieve anything if there are barriers of mental do’s and don'ts - therein I feel lies the attitude of the English in general to Art - it is akin to the attitude to sex - they see it as naughty and when they indulge in it they have the book of rules.’

Whilst perhaps all organised societies have, to some extent, distrusted artistic freedoms Kenneth Lauder pursued them with vigour and conviction for his whole life. His early paintings retain that youthful optimism, poetically poised for a life time of discovery and revelation.

Denys J. Wilcox